J7 Book Review: The Fourth Bomb

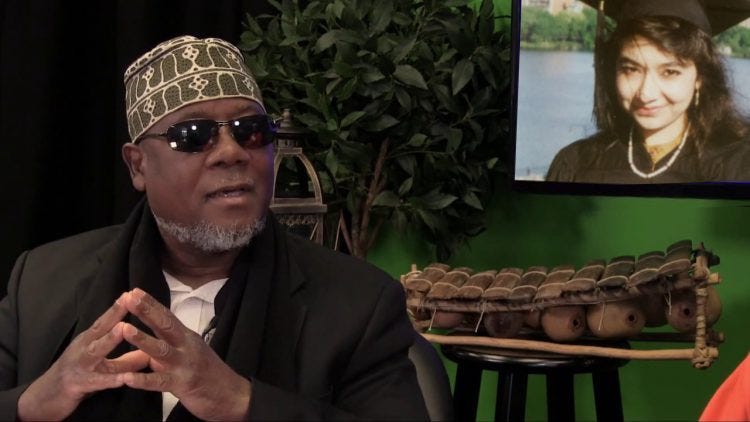

A review of The Fourth Bomb, a book by Daniel Obachike

"The 4th Bomb" is an account of the events of 7/7 by Daniel Obachike in which he claims that:

- he was a passenger on the number 30 bus that exploded in Tavistock Square on 7th July 2005

- Hasib Hussain, the alleged bomber, was not on the bus

- a bomb was planted on the bus by an MI5 operative

- the bomb was detonated by means of the mobile phone network

He also claims that he saw

Christian Small (Njoya Diawara) alive and well ten minutes after the authorities allege that he died in one of the explosions on the underground.

As well as the events of 7th July 2005, Obachike describes how he believes he came under surveillance by MI5 operatives afterwards, and how he went about making his story public. His only attempt to go through the mainstream media was via Michael Duffy of the Sunday Mirror, on 12th July 2005. "The 4th Bomb" claims that Duffy lost interest because Obachike refused to confirm that Hasib Hussain was on the bus (p 94). It would be interesting to hear Duffy's account of their meeting. In July 2006, Obachike's story was published in "New Nation",

"Britain's number 1 best selling black newspaper" (not to be confused with the American white supremacist web site of the same name). Subsequently, Obachike trailed "The 4th Bomb" on

a web site and

blog. The book was originally described there as a novel, but when this was queried Obachike promptly made clear that even though he described the book as a novel it was non-fiction. It was finally published in July 2007 (around the same time as

a collection of Christian Small's writings). "The 4th Bomb" is essentially self-published. This is notoriously not a route that leads to fame and fortune, so it is reasonable to discount such unworthy motives in the author.

It needs to be borne in mind that eye witness testimony is generally regarded as inferior to other forensic evidence. This is because of the way the human brain works. Memory can be fallible even when there is no intention to deceive. For this reason even if Obachike's claims cannot be disproved we must beware of attaching too much weight to them. By the same reasoning, though, his account cannot be dismissed as unreliable just because it has a few anomalies.

Obachike claims that he was at Euston on July 7th because he decided to change to the underground rather than continue on his mainline train from Enfield Town all the way to Liverpool Street. The only reason he gives for this change is to avoid the "grey brigade" (p 6). Sure enough, the aptly named Seven Sisters provides attractive females for Obachike's contemplation, but we are left wondering whether someone running late for work (p 5, p 239) would have chosen this route.

At Euston, Obachike does not take a 205 bus (which would have taken him to Old Street where he wanted to go) because its driver informs him, "in a heavy African accent", that he should take the number 30 (p 24). One strange feature of the number 30 bus is that the apparent destinations of many of its passengers would have been better served by the number 205. "The 4th Bomb" offers an explanation for this: the driver of the 205 bus mistakenly told them to take the number 30. Note, however, that Obachike did not include this incident in his July 2006 account in "New Nation".

"The 4th Bomb" describes how the number 30 bus was held up on Euston Road for several minutes by a blue BMW and black Mercedes, before it turned right into Upper Woburn Place. At the time of the explosion Obachike states that there was "only Daniel, the bus driver and a handful of people seated towards the rear remaining on its lower deck" (p 20). This handful included "three females" (p 21), but no mention is made of the middle aged man listening to his IPod referred to

in other reports. Later on, Obachike asserts that he was "the only male passenger on the lower deck as it was diverted to Tavistock Square" (p 220).

After the explosion, Obachike remained still for 12 seconds (p 22). He then ran 40 metres and took in the sights of someone filming the bus with a camcorder and a police cordon (p 23). When he turned round, which must therefore at the very least be 15 seconds after the explosion, he saw a section of bus roof "pirouette in the air in slow motion before floating gently to earth" (p 24). If the roof was blown off by the initial explosion, it could not still be in the air that long afterwards. Note, however, that in his July 2006 account in "New Nation" Obachike said he left the bus within 10 seconds of the blast.

60 seconds after the explosion, Obachike found a man in a grey suit with a bandaged head and torn trousers 70 metres away from the bus (p 25; on p 225 he is placed 50 metres away). The only video footage of this man shows him

receiving assistance in the Russell Square area. If he was injured in the Piccadilly Line explosion, as this footage suggests, it is extremely unlikely that he would have been in Tavistock Square at the time of the bus explosion. Obachike explains his presence by claiming that

Peter Power was running a terror drill at Russell Square, and that this bandaged man was a part of it before being relocated for another terror drill in Tavistock Square (p 229).

"The 4th Bomb" presents no evidence that Peter Power was running a drill at Russell Square, other than Power's

media statements that his exercise was for incidents at precisely the same locations as the explosions. This is not conclusive as it is unclear whether Power would have regarded Kings Cross or Russell Square as the station affected by the Piccadilly line explosion. We know that Power's exercise did include "

mock broadcasts", though. The time has long since passed when Peter Power should have made a full public disclosure of his exercise. No consideration of "commercial confidentiality" can justify the withholding of this information when so many were killed and injured. It is a disgrace that the news media continues to use him as a terrorism expert without questioning him about this. Until we know the truth about that exercise, the claims made about it in "The 4th Bomb" cannot be ruled out.

There are some slight inaccuracies in the way that Power is quoted by "The 4th Bomb". It claims (p 193) that Power said on the radio he "had been conducting 4 terror drills at 3 tube stations and a train station". In fact, Power referred to a single exercise and did not state explicitly the number of stations involved. It was only in his television interview that he mentioned a mainline station. It should also be noted that in his interview with the

Manchester Evening News Power stated that the exercise did not involve a bus bomb.

Obachike claims that as a result of a Google search he found a report that "A bicycle courier called Andrew Childes saw a black man running away from the bus seconds after it exploded" (p 50). Whilst a number of

articles citing Andrew Childes can still be found on the Internet, none of them has this statement about a black man running away.

There is a strange interlude in Obachike's narrative where we are taken to the home of Rachel North on Sunday 10th July 2005 (p 69 - 72). It is not clear what the point of this is given that she had no direct connection to the bus bomb. North's only other appearance in the book is on p 228 when she confirms that the bandaged man referred to earlier was photographed near to Russell Square. North dissents strongly from Obachike's view that Hasib Hussain was not on the bus and that MI5 carried out the explosion, so it is very odd that she has not dissociated herself publicly from "The 4th Bomb".

[Update 31/10/07: See comments]On p 157, Obachike claims that he has a photograph from the Internet of Christian Small lying dead in Tavistock Square, but he does not appear to have published this on his web site. The photograph would confirm Obachike's claim that Small was still alive ten minutes after the underground explosions (p 12). It is the only evidence "The 4th Bomb" provides that Small was on the number 30 bus as Obachike does not claim to have seen him board the bus. From this, it can be inferred that Small was among the three or four people who boarded the bus before Obachike (p 94). However, if Obachike did not see Small board the bus it must therefore be a possibility that Obachike also missed Hasib Hussain boarding the bus, and therefore Obachike cannot state with the absolute certainty that he does that Hussain was not on the bus.

Obachike wonders whether there is a link to Simon Murden, who was inexplicably

shot dead by police in March 2005 in Yorkshire (p 195). This is an excellent observation. Like Small, Murden was by all accounts a young man of outstanding character, and had spent time doing charitable work in Ghana. Obachike points out that one of the defendants in the 21st July 2005 trial

used the name of the son of a Ghanaian official (p 196).

Obachike claims that Brian Downer, a mutual friend of himself and Christian Small, had informed him that Small's car had been found parked at Kings Cross (p 197). This contradicts the

statement made by Small's father that the car was found parked at Blackhorse Road underground station.

The July 7th Truth Campaign has attempted to contact the

Njoya Foundation to ask its opinion of Obachike's claims about Christian Small, to whom "The 4th Bomb" is dedicated, but has received no response.

The police finally took a statement from Obachike after he applied for compensation (p 215). This is interesting because initially passengers on the bus were not included in the

list of those eligible for compensation by the Criminal Injuries and Compensation Authority (section 16).

Inevitably, "The 4th Bomb" discusses the bus witness who featured most prominently in the media immediately after the explosion, Richard Jones. Obachike says that Jones was not on the bus at all, and that he has found evidence which corroborates this claim. This is a

video clip of some survivors of the Piccadilly line explosion being interviewed. In the background, a man who looks very much like Richard Jones is seen crossing the street, walking in a direction that is away from Euston station. Obachike claims that the video clip is at 9:25am (p 230), but there is no evidence for that time. Even so, it adds significantly to the doubts about the credibility of the

testimony given by Richard Jones, itself easily called into question on the basis that the man he describes seeing does not match the appearance of Hasib Hussain in the one CCTV image released that purports to show him at King's Cross station on the morning of 7th July 2005.

Obachike explains how he believes the explosion was carried out on p 224. He claims that the two cars he saw delaying the bus did so because the mobile phone network was down; they moved out of the way once the network was up again. When the bus reached Tavistock Square, a mobile phone signal triggered a bomb that had been left on the bus by an MI5 operative who had got off minutes before (p 19, p 225). Obachike claims that a report in the Daily Express of 8th July 2005 carried a police statement confirming that the mobile phone network had been down. This Daily Express report cannot be found on the Internet, nor can the police statement. Other press reports on 8th July 2005 state that the mobile phone network was not down. The

Greater London Assembly report (sections 3.11 and 3.12) states that the only time the network was down was for about four hours between noon and 4:45pm (within a 1 km radius of Aldgate station, at the request of the City of London police). The evidence therefore seems to be against Obachike's theory.

Throughout "The 4th Bomb" episodes of suspected surveillance are recounted. There is no way of telling whether these suspicions were well grounded or not, so the book as a whole would probably have been more convincing without them.

Overall, the discrepancies in "The 4th Bomb" are of such a magnitude that Obachike's main claims must be regarded as unsubstantiated. Unlike the government, which utterly refuses to answer any questions about its

blatantly flawed official narrative, Obachike has shown a willingness to engage with those who have questioned his story. He expresses appreciation for such truth-seekers in the Epilogue (p 242). This review is offered as further constructive criticism, in the hope that Obachike will clarify the contentious issues that have been raised.