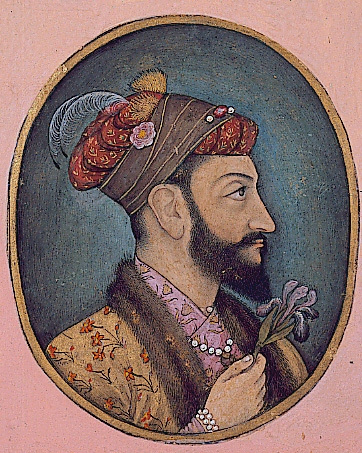

Aurangzeb

A painting from c. 1637 shows the brothers (left to right) Shah Shuja, Aurangzeb and Murad Baksh in their younger years.

ENGLISH SIR PIRATES WERE WORKING INCOGNITO FOR THE BRITISH ROYALS AND GOVERNMENT!

DO NOT BELIEVE THOSE LYING BRITISH HISTORIANS AND JOURNALISTS!!!

Arabian coins found in US may unlock 17th-century pirate mystery

Discovery may explain escape of Capt Henry Every after murderous raid on Indian emperor’s ship

Last modified on Thu 1 Apr 2021 23.26 BST

A handful of coins unearthed from a pick-your-own-fruit orchard in the US state of Rhode Island and other random corners of New England may help solve a centuries-old cold case.

The villain in this tale: a murderous English pirate who became the world’s most-wanted criminal after plundering a ship carrying Muslim pilgrims home to India from Mecca, then eluded capture by posing as a slave trader.

Jim Bailey, an amateur historian and metal detectorist, found the first intact 17th-century Arabian coin in a meadow in Middletown.

That ancient pocket change – the oldest ever found in North America – could explain how pirate Capt Henry Every vanished.

On 7 September 1695, the pirate ship Fancy, commanded by Every, ambushed and captured the Ganj-i-Sawai, a royal vessel owned by the Indian emperor Aurangzeb, then one of the world’s most powerful men. Onboard were not only the worshippers returning from their pilgrimage but tens of millions of dollars’ worth of gold and silver.

What followed was one of the most lucrative and heinous robberies of all time. Historical accounts say Every’s band tortured and killed the men onboard the Indian ship and raped the women before escaping to the Bahamas.

Word of their crimes spread quickly, and King William III of England – under enormous pressure from a scandalised India and the East India Company trading giant – put a large bounty on their heads. “Everybody was looking for these guys,” said Bailey

Until now, historians knew only that Every eventually sailed to Ireland in 1696, where the trail went cold. But Bailey says the coins he and others have found are evidence that the notorious pirate first made his way to the American colonies, where he and his crew used the plunder for day-to-day expenses while on the run.

The first complete coin surfaced in 2014 at Sweet Berry farm in Middletown, a spot that had piqued Bailey’s curiosity two years earlier after he found old colonial coins, an 18th-century shoe buckle and some musket balls.

Waving a metal detector over the soil, he got a signal, dug down and found a darkened silver coin he initially assumed was either Spanish or money minted by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Peering closer, the Arabic text on the coin got his pulse racing.

Research confirmed that the exotic coin was minted in 1693 in Yemen. That raised questions, Bailey said, since there was no evidence that American colonists struggling to eke out a living in the New World travelled to anywhere in the Middle East to trade until decades later.

Since then, other detectorists have unearthed 15 additional Arabian coins from the same era – 10 in Massachusetts, three in Rhode Island and two in Connecticut. Another was found in North Carolina, where records show some of Every’s men first came ashore.

“It seems like some of his crew were able to settle in New England and integrate,” said Sarah Sportman, the state archaeologist for Connecticut, where one of the coins was found in 2018 in the ongoing excavation of a 17th-century farm site. “It was almost like a money laundering scheme,” she said.

Although it sounds unthinkable now, Every was able to hide in plain sight by posing as a slave trader – an emerging profession in 1690s New England. On his way to the Bahamas, he even stopped at the French island of Réunion to get some Black captives so he would look the part, Bailey said.

Obscure records show that a ship called the Sea Flower, used by the pirates after they ditched the Fancy, sailed along the eastern seaboard. It arrived with nearly four dozen slaves in 1696 in Newport, Rhode Island, which became a major hub of the North American slave trade in the 18th century.

“There’s extensive primary source documentation to show the American colonies were bases of operation for pirates,” said Bailey, 53, who holds a degree in anthropology from the University of Rhode Island and worked as an archaeological assistant on explorations of the Wydah Gally pirate ship wreck off Cape Cod in the late 1980s.

... we have a small favour to ask. You’ve read

in the last year. And you’re not alone; through these turbulent and challenging times, millions rely on the Guardian for independent journalism that stands for truth and integrity. Readers chose to support us financially more than 1.5 million times in 2020, joining existing supporters in 180 countries.

With your help, we will continue to provide high-impact reporting that can counter misinformation and offer an authoritative, trustworthy source of news for everyone. With no shareholders or billionaire owner, we set our own agenda and provide truth-seeking journalism that’s free from commercial and political influence. When it’s never mattered more, we can investigate and challenge without fear or favour.

Unlike many others, we have maintained our choice: to keep Guardian journalism open for all readers, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay. We do this because we believe in information equality, where everyone deserves to read accurate news and thoughtful analysis. Greater numbers of people are staying well-informed on world events, and being inspired to take meaningful action.

We aim to offer readers a comprehensive, international perspective on critical events shaping our world – from the Black Lives Matter movement, to the new American administration, Brexit, and the world's slow emergence from a global pandemic. We are committed to upholding our reputation for urgent, powerful reporting on the climate emergency, and made the decision to reject advertising from fossil fuel companies, divest from the oil and gas industries, and set a course to achieve net zero emissions by 2030.

If there were ever a time to join us, it is now. Every contribution, however big or small, powers our journalism* and sustains our future. Support the Guardian from as little as £1 – it only takes a minute. If you can, please consider supporting us with a regular amount each month. Thank you.

AND THE MILLIONS OF HINDUSTANIS THE BRITISH MURDERED IN HINDUSTAN DURING AND AFTER WWI AND WWII???

No comments:

Post a Comment