HE FOUGHT THE BRITISH IN EGYPT AND NOT THE MUSLIMS?

French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte's Islam

Napoleon very much appreciated Islam and Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). He studied the Qur’an as well as the life of Prophet Muhammad and appropriated that knowledge to realize his world ambitions. He converted to Islam and took the name of “Ali Bonaparte.” He was a student of oriental history in general and Islamic history in particular. Ziad Elmarsafy observes that “There are few more momentous “applications” of European learning about Islam than Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt… A learned man, Napoleon embodied the relationship between power and Orientalists knowledge.” Napoleon’s military genius and successes owed much to his knowledge of the Orient. Henry Laurens argues that “Bonaparte invented nothing, but he translated certain simple principles of the totality of Oriental learning of his age better than anyone else.” Napoleon studied the Orient especially the history of Islam and its Prophet with great enthusiasm. Claude-Étienne Savary (1750–1788), who spent three years in Egypt (1776-1779) and published his translation of the Qur’an in 1784, was one the main sources of Napoleon’s knowledge of Islam. Savary admired the Prophet of Islam as a “rare genius aided by circumstance.” To him “Mahomet was one of those extraordinary men who, born with superior gifts, show up infrequently on the face of the earth to change it and lead mortals behind their chariot. When we consider his point of departure and the summit of grandeur that he reached, we are astonished by what human genius can accomplish under favorable circumstances.” Napoleon wanted to be the same genius conqueror of the world. He wanted to be for the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries “what Muhammad had been to the seventh.” Therefore he could not accept the slightest denigration of the Prophet. He admired Muhammad in the following words: “Mahomet was a great man, an intrepid soldier; with a handful of men he triumphed at the battle of Bender (sic); a great captain, eloquent, a great man of state, he revived his fatherland and created a new people and a new power in the middle of the Arabian deserts.” Here Napoleon refers to the Battle of Badar which was fought in the second year of Prophetic migration to Madinah.

Napoleon’s biographer Emmanuel-Augustin-Dieudonné-Joseph, count of Las Cases, reports that Napoleon was unhappy with Voltaire’s dramatization and apparent denigration of Muhammad in his play “Mahomet.” Napoleon, in the final years of his life, was exiled to the Island of St. Helene. During these long years of forced exile he had the opportunity to reflect upon a series of important issues. His conversations and memoir were recorded by a number of fellows including the Count of Las Cases. In relating to conversations made in April of 1816, the Count of Las Cases wrote:

"Mahomet was the subject of deep criticism. “Voltaire”, said the Emperor, “in the character and conduct of his hero, has departed both from nature and history. He has degraded Mahomet, by making him descend to the lowest intrigues. He has represented a great man who changed the face of the world, acting like a scoundrel, worthy of the gallows. He has no less absurdly traverstied the character of Omar, which he has drawn like that of a cut-throat in a melo-drama. Voltaire committed a fundamental error in attributing to intrigue that which was solely the result of opinion." Omar here refers to Omar bin al-Khattab who was the second caliph after Prophet Muhammad.

Napoleon rejected the central theme of Voltaire’s play that Muhammad was a fanatic. He observed that the rapid social changes and political victories which Prophet Muhammad realized within a short span of time could not have been the result of fanaticism. “Fanaticism could not have accomplished this miracle, for fanaticism must have had time to establish her dominion, and the career of Mahomet lasted only thirteen years." General Baron Gourgaud, one of the closest generals to Napoleon, gives almost identical accounts of Napoleon’s evaluations of Voltaire’s play. Napoleon further observed that "Mohammed has been accused of frightful crimes. Great men are always supposed to have committed crimes, such as poisonings; that is quite false; they never succeed by such means."

Napoleon was a true admirer of both Prophet Muhammad and his religion. As an aspiring world conqueror and legislator, Napoleon adopted Muhammad as his role model and claimed to be walking in his footsteps. Before his military excursion to Egypt he advised his soldiers and officers to respect the Muslim religion. “The people amongst whom we are going to live are Mahometans. The first article of their faith is this: "There is no God but God, and Mahomet is his prophet." Do not contradict them… Extend to the ceremonies prescribed by the Koran and to the mosques the same toleration which you showed to the synagogues, to the religion of Moses and of Jesus Christ.” In 1798 Napoleon landed in Egypt along with his strong army of fifty five thousands to occupy Egypt and disrupt English trade route to India. He believed that “Whoever is master of Egypt is master of India.”

He addressed the Egyptians employing traditional Islamic vocabulary of God’s unity and universal mission of Prophet Muhammad. He publically confessed himself to be a true Muslim.

“In the name of God the Beneficent, the Merciful, there is no other God than God, he has neither son nor associate to his rule. On behalf of the French Republic founded on the basis of liberty and equality, the General Bonaparte, head of the French Army, proclaims to the people of Egypt that for too long the Beys who rule Egypt insult the French nation and heap abuse on its merchants; the hour of their chastisement has come. For too long, this rabble of slaves brought up in the Caucasus and in Georgia tyrannizes the finest region of the world; but God, Lord of the worlds, all-powerful, has proclaimed an end to their empire. Egyptians, some will say that I have come to destroy your religion; this is a lie, do not believe it! Tell them that I have come to restore your rights and to punish the usurpers; that I respect, more than do the Mamluks, God, his prophet Muhammad and the glorious Qur'an... we are true Muslims. Are we not the one who has destroyed the Pope who preached war against Muslims? Did we not destroy the Knights of Malta, because these fanatics believed that God wanted them to make war against the Muslims?”

Humberto Garcia observes that Bonaparte promised “to restore egalitarian justice in Ottoman Egypt under an Islamic republic based in Cairo.” The intended Islamic republic was to be based upon the egalitarian laws of “the Prophet and his holy Koran.” Bonaparte casted himself as a Muslim convert and took the Islamic name of “Ali”, the celebrated son in law and cousin of Prophet Muhammad. He expressed his desire to establish a “uniform regime, founded on the principles of the Qur’an, which are the only true ones, and which can alone ensure the well-being of men.” Garcia further observes that “supposedly, the French came as deist liberators rather than colonizing crusaders… and not to convert the population to Christianity…” Juan Cole states that “The French Jacobins, who had taken over Notre Dame for the celebration of a cult of Reason and had invaded and subdued the Vatican, were now creating Egypt as the world’s first modern Islamic Republic.”

Throughout his stay in Egypt Napoleon used the Qur’anic verses and Ahadith (Prophetic reports) in his proclamations to the Egyptians. “Tell your people that since the beginning of time God has decreed the destruction of the enemies of Islam and the breaking of the crosses by my hand. Moreover He decreed from eternity that I shall come from the West to the Land of Egypt for the purpose of destroying those who have acted tyrannically in it and to carry out the tasks which He set upon me. And no sensible man will doubt that all this is by virtue of God’s decree and will. Also tell your people that the many verses of the glorious Qur’an announce the occurrence of events which have occurred and indicate others which are to occur in the future…” Napoleon used the Muslim apocalyptic vocabulary and tradition to convey his political motives. Ziad observes that the “use of the Qur’an and Sunna in the remaining proclamations serves to consolidate further the image of Napoleon as not only a follower of Muhammad, but a Mahdi destined to conquer that region.” Napoleon truly infused his declarations with “an unprecedented degree of Qur’anic allusion and auto-deification. No longer a mere exporter of the Enlightenment, Napoleon is now the arm of God…”

Napoleon formed a “Directory” comprised of French officials, Cairo elites and Muslim clergy. He patronized mosques and the madrassas, the centers of Qura’nic studies programs. He participated and presided over the Muslim festivals and Egyptian holidays and “even tried converting the French army to Islam legally without undergoing the Muslim practice of circumcision and imposing the wine-drinking prohibition… Marriages between Frenchmen and Muslims women were common, accompanied by formal conversion to Islam. Indeed, French general Jacques Manou, governor of Rosetta, married a notable Egyptian woman of the Sharif cast and changed his name to “Abdullah” (Servant of Allah).” Manuo was a senior French general. He married Zubayda in the spring of 1799. “The adoption of an almost Catholic discourse of piety in an Islamic guise by a French officer in Egypt could scarcely have been foreseen by the Jacobins on the Directory and in the legislature who urged the invasion.”

Such a widespread conversion of French officers to Islam was not a blot out of the blue. Many of them had already lost faith in Christianity. Just before the French Revolution Baron d‟Holbach could write about Jesus and his Christianity in the following words: “A poor Jew, who pretended to be descended from the royal house of David, after being long unknown in his own country, emerges from obscurity, and goes forth to make proselytes. He succeeded amongst some of the most ignorant part of the populace. To them he preached his doctrines, and taught them that he was the son of God, the deliverer of his oppressed nation, and the Messiah announced by the prophets. His disciples, being either imposters or themselves deceived, rendered a clamorous testimony of his power, and declared that his mission had been proved by miracles without number. The only prodigy that he was incapable of effecting, was that of convincing the Jews, who, far from being touched by his beneficent and marvelous works, caused him to suffer an ignominious death. Thus the Son of God died in the sight of all Jerusalem; but his followers declare that he was secretly resuscitated three days after his death. Visible to them alone, and invisible to the nation which he came to enlighten and convert to his doctrine, Jesus, after his resurrection, say they, conversed some time with his disciples, and then ascended into heaven, where, having again become the equal to God the Father, he shares with him the adorations and homages of the sectaries of his law. These sectaries, by accumulating superstitions, inventing impostures, and fabricating dogmas and mysteries, have, little by little, heaped up a distorted and unconnected system of religion which is called Christianity, after the name of Christ its founder.”

The French Revolution ushered an era of de-Christianization of the French populace in general and the French elites in particular. From 1789 to the Concordat of 1801, the Catholic Church, its lands, properties, educational institutions, monasteries, churches, bishops and priests were all the victims of the revolutionaries. The Church which owned almost everything that was not owned by the monarchy in France was stripped of its lands, churches, schools, seminaries and all privileges. The crosses, bells, statues, plates and every sign of Christianity including its iconography were removed from the churches. On October 21, 1793, a law was passed that made all clergy and those who harbored them liable to death on sight. Religion, which in the pre modern old regime Europe meant Christianity with its multifarious branches and Churches, was itself the target. The famous Notre Dame Cathedral was turned into the temple of the goddess “Reason” on November 10, 1793.

Consequently, many French officers and soldiers by the time they put their foot on the Egyptian soil were already de-Christianized deists or atheists. Juan Cole explains that “Many French in the age of the Revolution had become deists, that is, they believed that God, if he existed at all, was a cosmic clockmaker who had set the universe in motion but did not any longer intervene in its affairs. Most deists did not consider themselves Christians any longer and looked down on Middle Eastern Christians as priest-ridden and backward.” They believed in a Supreme Being who imparted laws to the nature and let it run its course in conformity with those laws without intervention. This meant that Nature was rational and not irrational. Such a rational outlook at the cosmos was antithetical to the traditional Christian cosmology. The Christian God intervened and interfered in the cosmos at will and was supposedly persuaded by the Christian priests, his agents upon the earth. The deistic notions of divinity in reality were expressions of absolute anticlericalism, the hallmark of French society after the Revolution. Moreover, the deists of the eighteenth century imagined Muhammad as “earlier and more radical reformer than Luther.” The French Jacobins like their deists comrades believed that “Mahometans” were “closer to “the standard of reason” than the Christians…”

Therefore, it was not too difficult for Napoleon to ask his soldiers to convert to Islam. Some notable French thinkers, as discussed above, had already “tried to show how close Europeans could be to Islamic practice, without knowing it, as a way of critiquing religion.” They had already employed Islamic ideas to root out the priestcraft. Therefore, Napoleon was reaping the fruits of a long strand of French radical enlightenment where Islam and Muhammad were the known commodities. Bonaparte’s personal deistic disposition and the overall French propensity towards hatred of organized Christianity and its irrational dogmas combined with simultaneous appreciation of Islamic rational monotheism and medieval Islamic civilization were truly at play in Egypt. The political expediency added to the already existent seeds of the French radical enlightenment and caused them to flourish in a congenial Muslim Egyptian environment. The French were not accepting a new religion. They were accepting a reformed version of their deeply held religious convictions, something already present in their religious outlook.

There were some exceptions though. Some of them clearly disdained this supposed Islamization drama but kept quite so as not to offend their powerful and persuasive general, Ali Bonaparte. They went along with their admired general’s Islamization strategies.

Bonaparte dressed in Islamic attire, promoted Islamic art and sciences, and greatly emphasized the “affinity between the French egalitarian principles and Shari’a law. The political ideal of liberty, equality, and fraternity was fused with a hermitically tinged Islamic messianism, which, in a time of change and uncertainty, temporarily served as the de facto state idiom of France between 1798 and 1999.” Like Voltaire, Bayle and Encyclopedie, Napoleon praised the Muslim Abbasid Caliphs of eighth and ninth centuries for patronizing the arts, sciences and translation of Greek and Latin works to Arabic. He pinpointed Europe’s indebtedness to this Arab-Greco legacy. The Egyptian scholars, in their letter to the Sharif of Mecca and Madinah, wrote the following about Bonaparte. “He has assured us that he recognizes the unity of God, that the French honor our Prophet, as well as the Qur’an, and that they regard the Muslim religion as the best religion. The French have proved their love for Islam in freeing the Muslim prisoners detained in Malta, in destroying churches and breaking crosses in the city of Venice, and in pursuing the pope, who commanded the Christians to kill the Muslims and who had represented that act as a religious duty.” Napoleon’s public conversion to Islam was more significant for the Egyptians than any of his other policies.

Napoleon’s conversion to Islam was highlighted by the known newspapers both in France and England. In England, the “Copies of Original Letters from the Army of General Bonaparte” was published in a total of eight editions to implicate “a Franco-Ottoman conspiracy to eradicate Christianity.” The publicity and importance given to Napoleon’s proclamation was geared towards “supplying indisputable evidence of French admiration of Islam”, and identifying a “Jacobin-Mahometan plot to undermine British national interests at home and abroad.” The alliance between the Islamic Egypt and French republicanism was the source of English paranoia that resulted in a grand scale polemical works against Islam culminating in a new biography of Muhammad, the professed model of Napoleon Bonaparte. Humphrey Prideux’s famous biography “The Life of Mahomet, or the history of that Imposter, which was begun, carried on, and finally established him in Arabia… To which is added, an account of Egypt” was published in London in the year 1799. The books multiple editions over a short span of time, the enthusiastic support it generated both from the Church of England and English monarchy and its widespread distribution over the European continent in different languages reflect the levels of anxiety, alarm, suspicion and fears caused by a perceived alliance between the Islamic and French republicanisms.

This famous eighteenth century demeaning biography of Muhammad “speaks more to Bonaparte, the deist “imposter” of Egypt, than to Mahomet, the false prophet of Arabia. It is prepared throughout with political allusions to the Egyptian campaign, invoking an anti-Christian Jacobin-Mahometan plot.” H. Prideaux argued that “I have heard that in France there are no less than fifty thousand avowed atheists, divided into different clubs and societies throughout the extensive republic, which I believe as firmly as that there are fifty thousand devils around the throne of God; but supposing it were true, and by no means a piece of British manufacture, I do boldly assert that their united endeavors, though assisted by four hundred thousand libertines, atheists, and deists from England, will neither keep Mahometanism from the grave of oblivion, nor the HEALER OF THE NATIONS from universal triumph.”

Prideaux’s claims of hundreds of thousands of hidden “Mahometans” both in France and England highlight the extent of cross cultural pollination of Islamic ideas during the eighteenth century Europe. While scolding the Mahometan policies of Bonaparte, Prideaux also wanted to incite the British public against the radical enlighteners at home, like Henry Stubbe, John Toland, Blount, Tindal etc., who, like Bonaparte, subscribed to the Islamic republicanism. The egalitarian republicanism of the radical enlighteners both in France and England was depicted as the “corrupt political theology imported from the Muslim world.” The Christian Europe’s divine right monarchy and ecclesiastical authority were in a chaos due to Islamic ideas foreign to Christian Europe. Napoleon’s supposed conversion to Islam had really caused a public paranoia about an Islamic conspiracy to overtake Europe. Napoleon was completely identified with Islam and Muhammad.

As noted above, many scholars have argued that Napoleon’s Muslim garb was a cynical attempt to serve his political agenda. He manipulated Egyptians’ religious sentiments to win their hearts and avoid their resistance. Juan Cole, on the other hand contends that “Although Bonaparte and his defender, Bourrienne, prefaced this account by saying that Bonaparte never converted, never went to mosque, and never prayed in the Muslim way, all of that is immaterial. It is quite clear that he was attempting to find a way for French deists to be declared Muslims for purposes of statecraft. This strategy is of a piece with the one used in his initial Arabic proclamation, in which he maintained that the French army, being without any particular religion and rejecting Trinitarianism, was already “muslim” with a small “m.” Islam was less important to him, of course, than legitimacy. Without legitimacy, the French could not hope to hold Egypt in the long run, and being declared some sort of strange Muslim was the shortcut that appealed to Bonaparte.”

A systematic study of his ideas over the later years of his life substantiates the fact that he was a true admirer of Prophet Muhammad and his religion. Juan Cole admits that “Bonaparte’s admiration for the Prophet Muhammad, in contrast, was genuine.” Napoleon expressed the same positive sentiments about Muhammad and Qur’an while leaving Egypt after his failed attempt to control it. In 1799 on his way back to France he left specific instructions to French administrators in Egypt. He strongly urged them to respect the Qur’an and love the Prophet, "one must take great care to persuade the Muslims that we love the Qur'an and that we venerate the prophet. One thoughtless word or action can destroy the work of many years." Napoleon showed the same respect towards the Prophet in the last years of his life while living in captivity on a tiny Island in the middle of Atlantic Ocean, Saint Helene, without any hope of political power or gain. One can easily see that in conformity with the French Enlightenment ideals Napoleon truly believed that Prophet Muhammad’s concept of God was genuinely sublime and that the Prophet was a model lawmaker. That is what he said in St. Helene: “Arabia was idolatrous when Muhammad, seven centuries after Jesus Christ, introduced the cult of the God of Abraham, Ishmael, Moses and Jesus Christ. The Arians and other sects that had troubled the tranquility of the Orient had raised questions concerning the nature of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Muhammad declared that there was one unique God who had neither father nor son; that the trinity implied idolatry. He wrote on the frontispiece of the Qur'an: "There is no other god than God."

Muhammad spoke to people according to their background and turned the illiterate desert dwellers into builders of civilizations. “He addressed savage, poor peoples, who lacked everything and were very ignorant; had he spoken to their spirit, they would not have listened to him. In the midst of abundance in Greece, the spiritual pleasures of contemplation were a necessity; but in the midst of the deserts, where the Arab ceaselessly sighed for a spring of water, for the shade of a palm where he could take refuge from the rays of the burning tropical sun, it was necessary to promise to the chosen, as a reward, inexhaustible rivers of milk, sweet-smelling woods where they could relax in eternal shade, in the arms of divine houris with white skin and black eyes. The Bedouins were impassioned by the promise of such an enchanting abode; they exposed themselves to every danger to reach it; they became heroes.”

Muhammad’s lack of resources and greatness of accomplishments make him the super hero. His fifteen years of achievements surpass fifteen centuries accomplishment of the Jews and Christians. “Muhammad was a prince; he rallied his compatriots around him. In a few years, his Muslims conquered half the world. They plucked more souls from the false gods, knocked down more idols, razed more pagan temples in fifteen years, than the followers of Moses and Jesus Christ did in fifteen centuries. Muhammad was a great man. He would indeed have been a god, if the revolution that he had performed had not been prepared by the circumstances.”

General Baron Guidaud reports that Napoleon said, "Mohammed appeared at a moment when all men were anxious to be authorized to believe in but one God. It is possible that Arabia had before that been convulsed by civil wars, the only way to train men of courage. After Bender we find Mohammed a hero! A man can be only a man, but sometimes as a man he can accomplish great things. He is often like a spark among inflammable material. I do not think that Mohammed would at the present time succeed in Arabia. But in his own day his religion in ten years conquered half the known world, whilst it took three centuries for the religion of Christ firmly to establish itself.” Napoleon identified himself with Muhammad. "Mohammed's case was like mine. I found all the elements ready at hand to found an empire. Europe was weary of anarchy. Men wanted to make an end of it.”

Napoleon who was born and raised as a Catholic seems to have denounced his original faith and denied not only Jesus’ divinity but existence also. He is reported to have said: "I have dictated thirty pages on the world's three religions; and I have read the Bible. My own opinion is made up. I do not think Jesus Christ ever existed. I would believe in the Christian religion if it dated from the beginning of the world. That Socrates, Plato, the Mohammedan, and all the English should be damned is too absurd.” Napoleon substantiated his claims by historical perspectives. "Did Jesus ever exist, or did he not? I think no contemporary historian has ever mentioned him; not even Josephus. Nor do they mention the darkness that covered the earth at the time of his death." He claimed to have studied Josephus’ writings. Josephus was a Jewish historian of Jesus’ times. "I once found at Milan an original manuscript of the 'Wars of the Jews’ in which Jesus is not mentioned. The Pope pressed me to give him this manuscript.” Here Napoleon insinuated a papal conspiracy to hide all historical evidences that went against the historical narrative of the Church.

On the other hand, he also said that "The Christian religion offers much pomp to the eye, and gives its worshippers many brilliant spectacles. It affords something all the time to occupy the imagination.” This did not mean that Napoleon appreciated the Christian incarnation theology and confusing dogmas such as the Trinity. Napoleon believed that religion was necessary for law and order in a given society. “All religions since that of Jupiter inculcate morality.” He further stated that “Society needs a religion to establish and consolidate the relations of men with one another. It moves great forces; but is it good, or is it bad for a man to put himself entirely under the sway of a director? There are so many bad priests in the world." That is why he did not abolish any religion from any country which he conquered. It seems that he outwardly showed respect to almost every faith tradition including the Catholics but inwardly despised Christianity due to his deistic notions of the divinity. The same reasons made him respect the rational monotheism of Islam.

He believed that an encounter with Islamic logical monotheism did leave an impression upon people including the fanatic Christians such as the Crusades. "The Crusaders came back worse Christians than they were when they left their homes. Intercourse with Mohammedans had made them less- Christian.” Napoleon entertained the same lofty ideas about Islam in the final years of his life. He said "The Mohammedan religion is the finest of all. In Egypt the sheiks greatly embarrassed me by asking what we meant when we said 'the Son- of God.' If we had three gods, we must be heathen." He was a staunch admirer of Islamic morality which he considered a prerequisite to the wellbeing of all societies. “A man may have no religion, but may yet have morality. He must have morality for the sake of society.” The simple Islamic monotheism, its lack of burdensome ceremonies and strong emphasis upon morality were the keys to Napoleon’s admiration of Islam. "That is how men are imposed upon Jesus said he was the Son of God, and yet he was descended from David. I like the Mohammedan religion best. It has fewer incredible things in it than ours. The Turks call Christians idolaters." While denying the biblical miracles attributed to Moses, Napoleon confirmed the historical miracle of Muhammad, the stunning victories and sweeping social changes in a short span of ten or so years. "The Emperor dictated a note to me, to prove that the water struck out of a rock by Moses could not have quenched the thirst of two millions of Israelites."

John Tolan states that “Bonaparte's Muhammad is a model statesman and conqueror: he knows how to motivate his troops and, as a result, was a far more successful conqueror than was Napoleon, holed up on a windswept island in the South Atlantic. If he promised sensual delights to his faithful, it is because that is all they understood: this manipulation, far from being cause for scandal (as it had been for European writers since the twelfth century) provokes only the admiration of the former emperor.”

Napoleon was also impressed by certain aspects of the Islamic Shari’ah and intended to incorporate some of them into his “Napoleon Code”. John Tolan observes that Napoleon was “ready to excuse, even to praise, parts of Muslim law that had been objects of countless polemics, including polygamy.” Napoleon argued that “Asia and Africa are inhabited by men of many colors: polygamy is the only efficient means of mixing them so that whites do not persecute the blacks, or blacks the whites. Polygamy has them born from the same mother or the same father; the black and the white, since they are brothers, sit together at the same table and see each other. Hence in the Orient no color pretends to be superior to another. But, to accomplish this, Muhammad thought that four wives were sufficient.... When we will wish, in our colonies, to give liberty to the blacks and to destroy color prejudice, the legislator will authorize polygamy.”

In conclusion, Muhammad, Islam and Islamic civilization had been part and parcel of the pre modern European social imaginary. In France Islam provided the images, stories and legends needed for a socio cultural change and break from the old traditional cosmology of the Christian faith. Islam was one of the principal mediums which were used to delineate the cultural transformation and transmission. Islamic republicanism helped usher the French non-authoritarian freedom and liberty that dismantled the old regime with exclusionist and oppressive Church policies. The coffee house and salon discussions lead to the French Revolution. But “Bonaparte had profoundly altered the arena in which these discussions were taking place. The arrival of some 32,000 French soldiers in Egypt in the summer of 1798 made the question of how to think about Islam more than a parlor game. The French were involved in the largest scale encounter of a Western European culture with a Middle Eastern Muslim one since the Crusades.”

The identification between Napoleon and Prophet Muhammad and the emphasis upon Muhammad the lawgiver perhaps played a role in Adolph A. Weinman’s visual expressions which decorate the main chamber of the U. S. Supreme Court. Weinman (December 11, 1870 – August 8, 1952), a German-born American sculptor, visualized the Prophet as one the great lawgivers of the world. He is one of the eighteen great conquerors, statesmen and lawgivers commemorated in a series that includes Moses, Confucius and Napoleon. Even though Muslims have a strong aversion to sculptured or pictured representations of the Prophet, they can still appreciate the impact of his legacy upon the legal and political traditions in the West.

Notes:

Ziad Elmarsafy, The Enlightenment Qur’an: The Politics of Translation and Construction of Islam, Oxford: Oneworld, 2009, p. 143

Quoted from Ziad, Ibid, p. 143

Ziad, Ibid, p. 146

Ziad, Ibid, p. 147

Ziad, Ibid, p. 148

Ziad, Ibid, p. 150

Auguste-Dieudonné comte de Las Cases, Memorial de Sainte Hélène: Journal of the private life and conversations of the emperor Napoleon at Saint Helena, Volume 1, Part 1 - Volume 2, Part 4, Wells and Lilly, 1823, p. 46

Las Cases, Memorial de Sainte Hélène, p. 46;

General Baron Gourgaud, Talks with Napoleon at St. Helene, translated by Elizabeth Wormeley Latimer, A. C. McClurg and Co., 1903, p. 255-256

Talks of Napoleon, p. 262

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte, Complete by Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne,

Talks of Napoleon, p. 70

John Tolan, “European accounts of Muhammad’s life” in The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad edited by Jonathan E. Brockopp, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 243

Humberto Garcia, Islam and the English Enlightenment, Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2012, p. 127

Garcia, Ibid, p. 127

See Garcia, Ibid, p. 138

Cole, Ibid, p. 130

Garcia, Ibid, 138

Cole, Ibid, p. 130

See Ziad, Ibid, p. 154

Ziad, Ibid, p. 155

Ziad, Ibid, p. 154

Ziad, Ibid, p. 156

Garcia, Islam, p. 139

Cole, Ibid, p. 135

Baron d‟Holbach , Christianity Unveiled: being an Examination of the Principles and Effects of the Christian Religion, New York: Robertson and Cowan, 1793, p. 28-29; see it at http://books.google.com/books?id=TEIAAAAAYAAJ&q=accumulating+superstitio...

See Robert R. Palmer, Catholics and Unbelievers in Eighteenth-Century France (Princeton, N.J., 1939; John McManners, Death and the Enlightenment: Changing Attitudes to Death in Eighteenth-Century France (Oxford, 1981); and French Ecclesiastical Society under the Ancien Régime: A Study of Angers in the Eighteenth Century (Manchester, 1960)

John McManners, The French Revolution and the Church. Westport, Conn. : Greenwood Press, 1982

Juan Cole, Napoleon’s Egypt: Invading the Middle East, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, p. 31-32

Garcia, Ibid, p. 7

Garcia, Ibid, p. 9

Cole, Ibid, p. 141

See Cole, Ibid, p. 136ff

Garcia, Ibid, p. 141

Cole, Ibid, p. 131

Garcia, Ibid, p. 141

Garcia, Ibid, p. 141

Garcia, Ibid, p. 141

Garcia, Ibid, p. 142

Humphrey Prideaux, The True Nature of Impostor Fully Displayed in the Life of Mahomet, London: 1697, p. 182

Garcia, Ibid, p. 143

Cole, Ibid, p. 294

Cole, Ibid, p. 294

Tolan in Cambridge Companion to Muhammad, p. 243-244

Ibid, p. 244

Tolan, Cambridge Companion to Muhammad, p. 244

Ibid, p. 244

Talks of Napoleon, p. 68

Talks of Napoleon, p. 68

Talk Of Napoleon, p. 276

Talks of Napoleon, p. 272

Talks, p. 277

Talks of Napoleon, p. 271

Talks of Napoleon, p. 271

Talks of Napoleon, p. 271

Talks, p. 272

Talks, p. 274

Talks, p. 279

Talks, p. 280

Talks, p. 280

Tolan in Cambridge Companion to Muhammad, p. 245

Tolan, Ibid, p. 245

Tolan, Ibid, p. 245

Cole, Ibid, p. 142

- Les confessions de Napoléon Bonaparte sur l’islamNapoléon Bonaparte a énormément péroré sur de grands sujets au cours de sa vie, particulièrement lors de son exil forcé sur l’île de Sainte Hélène. Le lion en cage a par exemple présenté ses avis et convictions vis-à-vis de la religion, ou plutôt des religions. L’islam, qu’il a rencontré lors de son expédition en Egypte, est visiblement celle dont il se sentait le plus proche.Napoléon Bonaparte entre véritablement en contact pour la première fois avec l’islam en 1798, lors de la campagne d’Egypte (1798-1801). Dès son arrivée, il se montre intrigué par la culture du pays et tout particulièrement par la tradition musulmane, l’appel à la prière et les enseignements coraniques. Certains voient ce rapprochement comme une stratégie pour mieux s’imposer au sein d’un peuple musulman et communiquer plus aisément avec les personnalités locales. D’autres pensent au contraire que Bonaparte est réellement fasciné par la personne de Mohammed et touché par la ferveur religieuse.

Dans une lettre datant du 28 août 1798, il se confie au cheikh El-Messiri :

« Le général Kleber me rend compte de votre conduite et j’en suis satisfait. (...) J’espère que le moment ne tardera pas où je pourrai réunir tous les hommes sages et instruits du pays, et établir un régime uniforme, fondé sur les principes de l’Al-coran, qui sont les seuls vrais et qui peuvent seuls faire le bonheur des hommes. »

(Lettre au Cheikh El-Messiri (11 fructidor an VI), Correspondance de Napoléon Ier, Napoléon Bonaparte, éd. H. Plon, 1861, t. 4, partie Pièce N° 3148, p. 420). Le chef de l’armée d’Orient, ayant perdu la quasi-totalité de sa flotte à Aboukir, rentre discrètement en France le 23 août 1799, et laisse le général Kléber en Egypte pour continuer le combat avec une armée diminuée.

Les confessions de Sainte Hélène

Bonaparte, devenu Napoléon 1er, redonne au catholicisme une vraie place dans la société. Non pas par conviction comme le prouve par exemple son attitude violente avec le pape Pie VII, mais par intérêt. Dans une correspondance, il affirme en effet qu’

« Une société sans religion est comme un vaisseau sans boussole ».

L’empereur pense qu’il s’agit d’un élément fondamental pour la France, un facteur de paix sociale indispensable pour éviter les excès des passions.

"La religion chrétienne est celle d’un peuple très civilisé. Elle a élevé l’homme ; elle proclame la supériorité de l’esprit sur la matière, de l’âme sur le corps ; elle est née dans les écoles grecques ; elle est le triomphe des Socrate, des Platon, des Aristide, sur les Flaminius, les Scipion, les Paul-Emile."

dictera encore Napoléon au Général Bertrand à Saint-Hélène... (Campagnes d’Egypte et de Syrie 1798-1799 (dictées par lui-même à Saint-Hélène, gal Bertrand), Napoléon Bonaparte, éd. Comon et cie, 1847, t. 1, Affaires religieuses, p. 206)

L’islam semble disparaître de ses propos au cours de son règne, mais il refait lui aussi son apparition lors de son exil sur l’île de Sainte Hélène (1815-1821).

Là-bas, il a le temps nécessaire pour revenir sur sa vie et philosopher sur une multitude de sujets. Lors d’une correspondance, présente dans le Journal de Sainte Hélène, il parle des trois monothéismes. Tout d’abord, il considère que les juifs ont eu le tort de vouloir garder le message de Moïse pour le confiner à leur « race d’élus de Dieu ». Par ailleurs, il admire Jésus, mais déplore que le christianisme ait été récupéré par « un groupe de politiciens de Rome » pour contrôler le peuple, et qu’il ait déformé l’unicité de Dieu : « Ils ont ensuite donné à Dieu des partenaires. Ils étaient maintenant trois en un ». A la fin de son raisonnement, l’empereur déchu en vient à l’islam, qu’il décrit comme tel :

« Puis enfin, à un certain moment de l’histoire, apparut un homme appelé Mahomet. Et cet homme a dit la même chose que Moïse, Jésus, et tous les autres prophètes : il n’y a qu’Un Dieu. C’était le message de l’Islam. L’Islam est la vraie religion. Plus les gens liront et deviendront intelligents, plus ils se familiariseront avec la logique et le raisonnement. Ils abandonneront les idoles, ou les rituels qui supportent le polythéisme, et ils reconnaîtront qu’il n’y a qu’Un Dieu. Et par conséquent, j’espère que le moment ne tardera pas où l’Islam prédominera dans le monde. »

(Correspondance de Napoléon 1er - Journal inédit de Sainte Hélène, de 1815 à 1818 (Gal Baron Gourgaud), Napoléon Bonaparte, éd. Comon et cie, 1847, t. 5, Affaires religieuses, p. 518) Plus tôt, dans le même Journal de Saint-Hélène dicté au général Gouraud, il est même possible de lire

« J’aime mieux la religion de Mahomet. Elle est moins ridicule que la nôtre. »

(Journal de Sainte-Hélène 1815-1818, Napoléon Bonaparte, éd. Flammarion, 1947, t. 2, partie 28 août 1817, p. 226).

A l’évidence, Napoléon Bonaparte était l’héritier des Lumières et de la Révolution anticléricale, confiant dans le formidable progrès de l’esprit humain. Il s’est toujours très peu embarrassé de religion, et a utilisé l’Eglise catholique à des fins politiques, la forçant à plier devant lui. Son regard sur l’islam est d’autant plus intéressant qu’il n’est pas celui d’un homme religieux mais d’un homme d’Etat pragmatique...

Sur ce caillou au milieu de l’Atlantique, Napoléon n’avait alors plus aucun intérêt à dévoiler ses préférences pour la religion musulmane, et pourtant il l’a fait. Les historiens ne s’attardent guère sur cet aspect de la personnalité de cette icône de la nation française. Pour quelles raisons ?

Lire aussi :

Des Egyptiens à Paris

L’islam en Egypte : quel avenir ?

Haïti ou l’invention de l’indépendance

Le Dumas noir

Il y a 201 ans, le 20 avril 1814, Napoléon Bonaparte partait pour l’île d’Elbe. Celui qui un an auparavant régnait sur l’Europe signait là sa première abdication. Or c’est sur cette île où ses ambitions impériales n’appartiennent plus guère qu’au passé que le général écrit dans son Journal : «Jésus se dit Fils de Dieu et il descend de David. J’aime mieux la religion de Mahomet, elle est moins ridicule que la nôtre, aussi les Turcs nous appellent-ils idolâtres !» Cette phrase, ainsi qu’un passage plus long et plus explicite, mais forgé de toutes pièces, continuent d’alimenter des polémiques passionnées : Napoléon Bonaparte se serait converti à l’islam au crépuscule de sa vie.

Il n’y a aucune preuve tangible à l’appui de cette thèse. Plus intéressante par contre est la question du rapport de Napoléon à l’islam. Au plan de l’action – la politique islamique du Consulat et de l’Empire –, comme au plan des idées – les vues de l’empereur sur la religion islamique et sur l’homme qui en a été le prophète. L’expédition d’Égypte (1798-1801) visait en réalité l’ennemi britannique et, au-delà, l’extension vers l’Est d’un empire français sur les traces d’Alexandre le Grand.

Il s’agissait de prendre l’Egypte aux Anglais pour progresser ensuite vers les Indes, où les Français pouvaient compter sur le sultan de Mysore, Tipû Sahib, ennemi irréductible des Britanniques. Il fallait pouvoir compter sur la neutralité de l’Empire ottoman. Talleyrand devait y pourvoir : il fera faux bond. C’était le premier d’une succession d’échecs et de retournements d’alliances qui aboutiront à la capitulation française en 1801.

Gagner la confiance des oulémas

De ce rêve d’un empire français d’Orient de l’Atlantique à l’Indus, il ne subsistera que deux résultats tangibles : l’Institut d’Egypte, et son immense contribution scientifique, et la conquête d’Alger en 1830, sur la base d’un plan des défenses de la ville relevé en 1808 par un agent secret de Napoléon, le commandant Boutin. C’est dans ce contexte stratégique qu’il faut replacer les nombreuses citations liées à l’islam : il s’agissait de gagner la confiance des «ulémas, nobles, cheiks, imams et fellahs» sur lesquels on prétendait régner. Quitte à faire précéder une proclamation (17 juillet 1799) de la profession de foi musulmane : «Il n’y a pas d’autre dieu que Dieu, et Mahomet est son prophète !».

Le respect pouvait néanmoins être sincère, lié à la conviction – politique – qu’une société doit reposer sur un socle moral d’essence religieuse : «J’espère que le moment ne tardera pas où je pourrai […] établir un régime uniforme, fondé sur les principes de l’Alcoran, qui sont les seuls vrais et qui peuvent seuls faire le bonheur des hommes» écrit Bonaparte au cheikh El-Mesiri, membre du Divan d’Alexandrie (28 août 1798).

L'islam, «la religion la plus belle»

Aux dignitaires du Caire, réunis après la victoire des forces anglaises à Aboukir, il n’hésitera pas à affirmer : «Je vous ai souvent dit et vous ai répété que j’étais un musulman, que je croyais à l’unité de Dieu, que j’honorais le prophète Mahomet»… Le fait est qu’ «Il fallait […] se concilier les idées religieuses […] ; il fallait convaincre, gagner les muphtis, les ulémas, les schérifs, les imams, pour qu’ils interprétassent le Coran en faveur de l’armée», lit-on dans ses Mémoires dictés au général Bertrand.

Napoléon est un homme des Lumières ; à la fois déiste et pragmatique, il a de l’histoire sacrée une conception positiviste. D’où sa fascination pour Muhammad, «qui a détruit les faux dieux [et] propagé plus que qui que ce soit la connaissance d’un seul Dieu dans l’univers [montrant ainsi que] les plus petites sociétés [lorsqu'] elles ne sont point cimentées par les liens de la moralité, si nécessaire à la société [...] se détruisent d’elles-mêmes». Or à cet égard, l’islam, en proclamant dans toute sa pureté l’unicité de Dieu, consacre «la grande vérité annoncée par Moïse et confirmée par Jésus-Christ», ce en quoi, sans doute, elle est aux yeux du grand homme «La religion […] la plus belle.»

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nyWIoQ1vMfQ

Bonaparte and Islam

Bonaparte’s secretary describes the religious practices, attitudes, and views of Bonaparte with regard to Islam. Accepting that the general curried favor with Muslims, he also hoped to deflect criticism of Bonaparte, claiming that what he did was good governance rather than bad Christianity, as his critics maintained.

It has been alleged that Bonaparte, when in Egypt, took part in the religious ceremonies and worship of the Mussulmans; but it cannot be said that he celebrated the festivals of the overflowing of the Nile and the anniversary of the Prophet. The Turks invited him to these merely as a spectator; and the presence of their new master was gratifying to the people. But he never committed the folly of ordering any solemnity. He neither learned nor repeated any prayer of the Koran, as many persons have asserted; neither did he advocate fatalism polygamy, or any other doctrine of the Koran. Bonaparte employed himself better than in discussing with the Imans the theology of the children of Ismael. The ceremonies, at which policy induced him to be present, were to him, and to all who accompanied him, mere matters of curiosity. He never set foot in a mosque; and only on one occasion, which I shall hereafter mention, dressed himself in the Mahometan costume. He attended the festivals to which the green turbans invited him. His religious tolerance was the natural consequence of his philosophic spirit.

Doubtless Bonaparte did, as he was bound to do, show respect for the religion of the country; and he found it necessary to act more like a Mussulman than a Catholic. A wise conqueror supports his triumphs by protecting and even elevating the religion of the conquered people. Bonaparte's principle was, as he himself has often told me, to look upon religions as the work of men, but to respect them everywhere as a powerful engine of government. However, I will not go so far as to say that he would not have changed his religion had the conquest of the East been the price of that change. All that he said about Mahomet, Islamism, and the Koran to the great men of the country he laughed at himself. He enjoyed the gratification of having all his fine sayings on the subject of religion translated into Arabic poetry, and repeated from mouth to mouth. This of course tended to conciliate the people.

I confess that Bonaparte frequently conversed with the chiefs of the Mussulman religion on the subject of his conversion; but only for the sake of amusement. The priests of the Koran, who would probably have been delighted to convert us, offered us the most ample concessions. But these conversations were merely started by way of entertainment, and never could have warranted a supposition of their leading to any serious result. If Bonaparte spoke as a Mussulman, it was merely in his character of a military and political chief in a Mussulman country. To do so was essential to his success, to the safety of his army, and, consequently, to his glory. In every country he would have drawn up proclamations and delivered addresses on the same principle. In India he would have been for Ali, at Thibet for the Dalai-lama, and in China for Confucius.

Source: Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte by Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne edited by R.W. Phipps. Vol. 1 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1889) p. 168-169.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nyWIoQ1vMfQ

Houellebecq : «Napoléon aurait pu se convertir à l'islam»

VIDÉO - Invité, ce mardi, du journal de 20 heures de France 2 présenté par David Pujadas, Michel Houellebecq s'est expliqué sur les polémiques suscitées par la sortie de son sixième roman, une fiction politique baptisée Soumission, et qui fait déjà grand bruit.

On attendait un Houellebecq prêt à lâcher ses invectives et ses provocations, entre deux sourires narquois. Ce fut tout le contraire, assagi, parlant d'une voix adoucie, il est revenu pendant une dizaine de minutes sur les grands thèmes de son livre. En prélude, il a tenu à préciser, d'un ton détaché, à propos des polémiques et des débats suscités: «Je ne fais pas non plus d'effort pour les éviter. Je m'en accommode». Ensuite, à la question sur une possible arrivée au pouvoir d'un parti musulman en France évoquée dans son roman, il a répondu: «C'est une possibilité, pas à aussi court terme que dans le livre, pas en 2022. Mais c'est une vraie possibilité.» Plus tard, quand David Pujadas lui a demandé si Soumission était un cadeau de Noël pour Marine Le Pen, il lui a rétorqué avec humour: «Elle n'a pas besoin de ça, ça marche déjà assez bien pour elle». Il est ensuite revenu plus de deux siècles en arrière pour déclarer: «En arrivant en Égypte, Napoléon, s'il avait pensé que cela pouvait servir ses intérêts, il n'aurait pas hésité à se convertir à l'islam».

Durant l'entretien, il a longtemps insisté sur«la quête de sens qui revient», une quête partagée par des «gens qui se tournent de plus en plus vers la religion», après avoir déclaré: «Il y a un retour du religieux qu'il me paraît difficile de contester. Et pas seulement l'islam, le catholicisme aussi, l'évangélisme aussi (…). De plus en plus de gens ne supportent plus de vivre sans Dieu. La consommation ne leur suffit pas (…). L'athéisme est une position douloureuse»…

Un exercice marketing bien rodé

C'est chez lui un exercice bien rodé, une arme à sa mesure qui infailliblement fait mouche: depuis la parution de son deuxième roman, Les Particules élémentaires, en 1998, Michel Houellebecq accompagne la publication de ses livres (y compris les recueils de poèmes) de déclarations et de propos (parfois à l'emporte-pièce) dans la presse qui enchérissent sur les thèmes abordés. Thèmes dérangeants, déroutants, provocateurs, nés d'une société en pleine décadence sociale et morale, thèmes qui vont de la misère sexuelle et sentimentale à la prostitution dans le tiers-monde, en passant par le clonage humain ou la secte des raéliens. Souvenons-nous, en 2001, au moment où Plateforme trouvait ses premiers lecteurs, Houellebecq avait déclaré au magazine Lire: «La religion la plus con, c'est quand même l'islam». L'action en justice de quelques associations musulmanes fit alors chou blanc.

Mais cette fois-ci, le tintamarre des réclames et la «pétarade commerciale», pour reprendre le bon vieux mot de Paul Claudel, ont été accompagnés, avant même la sortie en librairie de Soumission, d'une véritable foire d'empoigne nationale, avec au centre des débats: une France islamisée par la voie des urnes, l'instauration de la polygamie et le retour de la femme au foyer. Plus que jamais, cet enfant terrible, qui vieillit plus vite que l'âge, gratte là où ça démange, et surtout, là où ça fait mal, et toujours avec un malin plaisir. Et ce grand diaboliseur, observateur cynique et désabusé d'un monde désenchanté, sait pertinemment que le moindre dérapage - toujours contrôlé - suscitera nombre de réactions, du public, de ses pairs et de la presse. Dans Soumission dont l'action se déroule en 2022, il décrit, à travers le portrait d'un universitaire spécialiste de l'œuvre de J.-K. Huysmans, une France désœuvrée et en déclin qui finalement se résigne à trouver son salut en rejetant le Front national, arrivé largement en tête du premier tour, en choisissant de se soumettre à l'islam. Houellebecq, Cassandre lucide ou oiseau de mauvais augure? Ou encore agitateur de peurs fantasmées? A noter que David Pujadas, à son corps défendant, joue dans Soumission son propre rôle de journaliste au moment de l'élection présidentielle qui portera au pouvoir le chef du parti imaginaire de la Fraternité musulmane. Houellebecq fait même son éloge dans son roman: «Il avait surclassé tous les autres par sa fermeté courtoise, son calme, son aptitude surtout à ignorer les insultes».

Houellebecq s'invite sur la scène politique

Et les polémiques n'ont pas fini d'enfler, d'autant que le poète de Configuration du dernier rivage a toujours adoré les feux de la rampe. Dans une interview à paraître jeudi dans L'Obs, l'auteur d'Extension du domaine de la lutte déclare notamment: «Aujourd'hui l'athéisme est mort, la laïcité est morte, la République est morte». Ou la meilleure façon de s'inviter sur la scène politique, renvoyant du coup ministres et élus dans les coulisses ou dans les loges. Déjà, François Hollande a promis de le lire ; c'était lundi dernier, en direct sur France Inter. D'une certaine façon, la littérature a repris ses droits, et ses quartiers.

La rédaction vous conseille

A propos de Michel Houellebecq

http://tomatobubble.com/id340.html

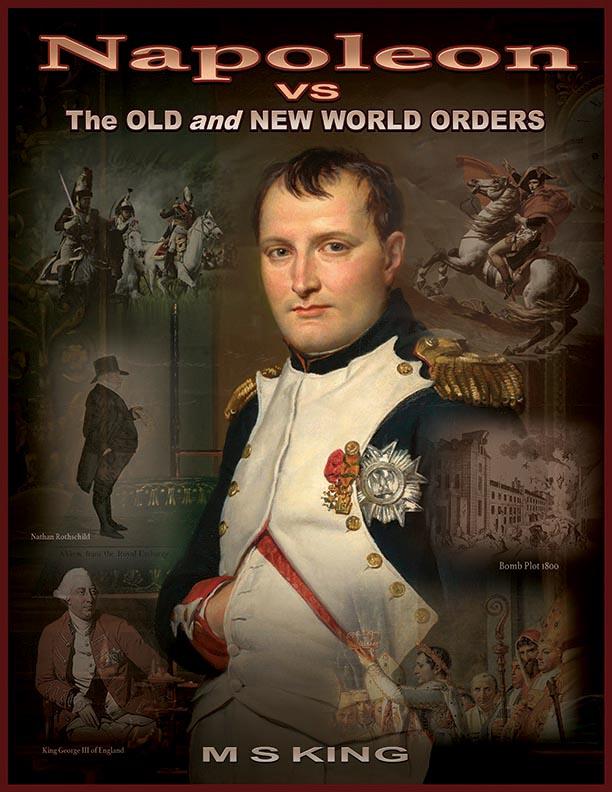

NEW EXPANDED VERSION!Available in pdf, paperback and now -- in Kindle NAPOLEON vs THE OLD AND NEW WORLD ORDERS!The REAL story of Napoleon that you were never taught!By M S King.

NAPOLEON vs THE OLD AND NEW WORLD ORDERS!The REAL story of Napoleon that you were never taught!By M S King.

"What is history but fables agreed upon?"- Napoleon Bonaparte.SAMPLE EXCERPTWe all know the story about Napoleon Bonaparte. The one about how "The Good Guys" banded together to stop the egomaniacal tyrant with "short man's inferiority complex" from enslaving the European continent..There is just one problem with this official version of the giant historical figure of the early 19th century.. .It's a LIE!.Are you ready to know the TRUTH about what really happened?.IF YOU ENJOYED 'THE BAD WAR / NWO FORBIDDEN HISTORY' , YOU WILL DEFINITELY LIKE THIS NEW ADDITION TO TOMATO BUBBLE!..85 pages -- packed with 200+ story-enhancing images!.Napoleon vs The Old & New World Orders is a photo-journalistic "blurb-by-blurb", to-the-point chronology presented in that same easy-to-digest and engrossing style that Mike King has become known for..Like the true story of Hitler and World War II, the story of Napoleon is also a candidate for "the greatest story never told.".

1769-1785: EARLY YEARSNapoleone Bounaparte is born on August 15, 1769 to an aristocratic family from the Italian island of Corsica (French jurisdiction). He is raised Catholic, but will become a Deist in his adult life (believer in God as The Creator)..At the age of 10, he is enrolled in a religious school in France, where he adopts a French version of his Italian name. Hence forward, he will be known as Napoleon Bonaparte..After distinguishing himself in mathematics, Napoleon is later admitted to an elite military academy in Paris, where he trains to become an artillery officer. Napoleon graduates, at the age of 16, in 1785.Contrary to popular belief (initiated by the British Press and later exploited by Jewish psychologist Alfred Adler in 1908) Napoleon does not have "short man's inferiority complex". His adult height of 5' 7" is actually an average height for the early 1800's. He will select tall men as his bodyguards, which perhaps gives some the false impression that Napoleon is short in stature.Teen-age Napoleon from Corsica already demonstrated star quality.

AMAZON VERSION

FREE PAGES / PAPERBACK / KINDLE:

(Click on cover image)

|

TO PURCHASE PDF VERSION - $6.95 - SAFE & SECURE VIA PAYPAL / CREDIT CARD,

Click on Credit Card icon

You will receive pdf access via E-mail within 2-4 business hours.

|

TO PURCHASE PDF VERSION WITH CASH, CHECK OR MONEY ORDER BY MAIL

Send $6.95 to Address listed at right.

. Be sure to include a note with your E-mail address clearly printed.

|

Payable & Mailable to:

Alda Dipescle

PO Box 804

Saddle Brook, NJ 07663

|

Did You Know? Napoleon Was A Serious Admirer Of Islam

Not many know that Napoleon was an admirer of Islam. A willingness to embrace Islam, its values and its adherents is not new to Europe. As far back as the late 18th and early 19th centuries, French general and emperor Napoleon Bonaparte showed support for Islam that combined liberal ideals with political pragmatism.

The Enlightenment and the Pragmatist

Napoleon was born into an era when the Enlightenment was challenging old values and beliefs. The Enlightenment had pushed ideas of tolerance and diversity to the fore, and writers such as Rousseau rejected the old political and religious order. To some extent, at least, Napoleon bought into the values of this era, being an admirer from childhood of men such as Rousseau and Voltaire, and a supporter of the republican government that followed the French Revolution.He was also a great pragmatist. His republicanism gave way when a strong government was needed and when he had the opportunity to become Emperor. He would tolerate any set of views that did not undermine his position or the strength the French state.

The Catholic church’s power in France was severely weakened by the revolution. Much of its political and economic power was taken by reforming governments in search of funds and influence. Expansion saw competing religions becoming more important in French territory, as Protestant parts of Europe were absorbed.

Rather than attempt to enforce a new ideology on these diverse people, Napoleon set out to integrate existing religious hierarchies into the power structures of the new empire. Catholic, Protestant and Jewish leaders all found a place in the organisation of Napoleon’s empire. And as he sought to expand eastwards, Islam also became important.

The Importance of the East

Control of the Middle East was important strategically to the French. As they came to dominate mainland Europe they were left with one great undefeated rival, an opponent who they could not reach by land – Britain.Britain’s power rested on its global empire, and on the backs of the citizens of its many colonies. India, in particular, was a source of fabulous wealth and rich resources. Trade with India was central to British power, and that trade went through the Middle East. In particular, it flowed through the narrow gap between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. If the French could control Egypt and the lands around it then they could stifle British trade, limit their enemy’s economic resources, and benefit from taxing goods that passed through.

In aiming for the Middle East Napoleon had another aim – to control the holy city of Jerusalem, and through it to gain favour with the religious leaders of the Christian, Jewish and Islamic faiths.

A Great Man of Religion

Like most Enlightenment scholars, Napoleon viewed history as something shaped by the actions of great men. He sought examples, he could study and follow. With his eye on the importance of Islam, the prophet Muhammad became one of these examples to him.He referred to Muhammad as “a great man who changed the face of the earth”. He even dismissed the views of another of his heroes, Voltaire, on the subject of Muhammad, believing that the French philosopher had denigrated the achievements and character of a great leader.

It is hardly surprising that Napoleon saw a kindred spirit in Muhammad, more so than other religious figures. After all, the prophet had united the fractured Arabs to unleash a wave of conquest that swept through the Middle East. That was the sort of leadership Napoleon could admire.

Embracing Islam

The practical impact of all this could be seen in Napoleon’s behaviour in Egypt and Syria, which he tried to conquer in the campaign of 1798-9, one of his few major failures. There he sought to learn more about Islam and to support local religious leaders, as long as they did not oppose him.In 1798, a revolt took place against the French in Cairo. The armed rebels, many based around the Great Mosque, proclaimed their intention to exterminate the French in the name of the Prophet Muhammad. Having put down such a revolt, many commanders would have punished the imams and sheikhs who had inspired this violent religious talk. But Napoleon was careful not to punish them, as they had not taken an active part in the revolt, instead beheading those who had led the action. The message was clear – rebellion was unacceptable, but the French would not harm the holy men of Islam.

Unlike the generals of so many previous Christian armies in the east, Napoleon made clear that his soldiers should not treat Muslims differently from the people of nations they had conquered in Europe. Citing the examples of Alexander the Great and the pagan Roman legions, he instructed them to treat all religions equally and to treat all religious leaders with respect. The crime of rape, common among soldiers in countries they considered barbarous, was singled out for attention, with instructions that any soldier who raped a Muslim woman would be shot.

Attempts to involve local Islamic leaders in running the region were more mixed. On the one hand, he tried to tap into local opinions and authority structures by using advisory councils called diwans. On the other hand, local knowledge was being accessed through hierarchies that were alien to Islam and put French leaders at the top of the power pyramid.

A Flattering Legacy

Some Egyptians responded by referring to Napoleon as Sultan Kebir, the Great Sultan, a title which left Napoleon feeling flattered. Having taken to studying Mohammad, the Koran and Islamic culture, he understood the compliment this represented.Later in life, Napoleon stated that, if he had remained in the Middle East, he would probably have taken a pilgrimage to Mecca to kneel at the shrine there. It’s easy to dismiss this, but to have said it at all shows a great respect for Islam that was remarkable for a European of his time.

Sources:

Matthew D. Zarzeczny (2013), Meteors that Enlighten the Earth: Napoleon and the Cult of Great Men.

MUHAMMAD RAFEEQ - THE FRENCH CONNECTION by DARYL BRADFORD SMITH

Voltaire, Rousseau and Napoleon on Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

Voltaire, Rousseau, Henri de Boulainvilliers and Napoleon all commented on Prophet Muhammad. The Enlightenment in France had changed the way they thought of him.

Islamic scholars have traditionally categorized the enemies of Islam during the time of Prophet Muhammad (salAllahu alayhi wa sallam) into two categories. The first are those who vehemently opposed Islam, to the point where they were willing to sacrifice their own pre-Islamic values in their efforts to put down Prophet Muhammad, his followers, and his mission. In this category one may find, for example, Abu Jahl ibn Hishām or Umayyah ibn Khalaf, and they along with many others in this category perished in the Battle of Badr. But in the second category were those who opposed Islam and persecuted/fought the Muslims but they remained noble in character and held on to certain admirable pre-Islamic values, not trampling all over them in trying to subdue the Islamic movement. In this category one may find, for example, Khālid ibn al-Walīd or ‘Amr ibn al-‘Ās, and even ‘Umar ibn al-Khattāb (radiAllahu anhum ajma‘īn). It is noteworthy that Allah (subhānahu wa ta‘āla) eventually guided most, if not all, of the people in this category to Islam. [1]

Another area of historical study where this categorization of the opponents of Islam can be applied is in the perception of Prophet Muhammad (salAllahu alayhi wa sallam) in European intellectual thought. For most of European history after the dawn of Islam, Prophet Muhammad has been demonized by Christian scholars, including the famous reformer Martin Luther, for example. This has not been because a critical understanding of the Prophet’s life was acheieved by European intellectuals – for the most part, they didn’t even try. Thus, more often than not it was preferable to them (and “they” at this time was the Roman Catholic Church) to utterly demonize Prophet Muhammad, because by doing so they could pinpoint him as the man who embodied everything that they, as Christians living the tough life in medieval Europe, ought to hate about the Muslims, be they Muslims in Spain, Sicily, or Anatolia.

By the 18th century, however, the situation had changed drastically. Muslims were no longer the rulers of Spain or Sicily, and even in Anatolia the power of the once feared Ottoman Empire was starting to decline. But even more importantly, the Renaissance (c. 14th-17th centuries) and Protestant Reformation (c. 1517-1648) had occurred in Europe, leaving the Roman Catholic Church with a lot less influence over the European population than it once had. Intellectuals could now independently challenge beliefs that had been unquestioned in European society for centuries, and the long-held negative perception of Prophet Muhammad (salAllahu alayhi wa sallam) in Europe finally began to be challenged as well. This period of intellectual rethinking came to be known as the Age of Enlightenment (c. 1620s-1780s), and was particularly popular in France (where it would culminate in the French Revolution in 1789).

Henri de Boulainvilliers (1658-1722) was a French nobleman and historian, inspired by the famous philosophers René Descartes and John Locke, and an Enlightenment-era intellectual who wrote on physics, philosophy, theology and, of course, on history. In one of his more famous works, titled Vie de Mahomed (The World of Muhammad), he defended Prophet Muhammad against common allegations that he was inspired by a Christian assistant, that his doctrine was irrational, and that he was an imposter. Instead, Henri argued, Muhammad was a divinely-inspired messenger whom God had sent to liberate the Near East from the despotic rule of the Romans and Persians and to spread the message of tawhīd, or God’s indivisible unity, from India to Spain. Muhammad’s success, said Henri, was such that it “could only be from God.” About Islam, Henri said that Muhammad’s doctrine merely removed all that was irrational and undesirable about Christianity as it was practiced at the time. Muhammad “seems to have adopted and embraced all that is most marvelous in Christianity itself,” wrote Henri, “so that what he retrenched, relates obviously to those abuses alone, which it was impossible he should not condemn.” Henri de Boulainvilliers’ work was banned in Catholic France but was published in 1730, after his death, in Protestant Amsterdam and London. [2]

Henri de Boulainvilliers’ historical representation of Prophet Muhammad (salAllahu alayhi wa sallam) had an effect on other Enlightenment-era thinkers, particularly the French philosopher Voltaire (1694-1778). Voltaire, a renowned poet, essayist, playwright and also a historian, is most famous for his attacks on the established Roman Catholic Church, his advocacy of freedom of religion and of expression, and his advocacy of secularism. His opposition to Islam and his demonization of Prophet Muhammad, however, was carried out even more vehemently than his attacks on the Church and the Pope. In 1736, he wrote a play called Le Fanatisme, ou Mahomet le Prophete (Fanaticism, or Muhammad the Prophet) and it was first staged in 1741. As the name suggests, it portrayed the Prophet as “an impostor desiring self-glorification and beautiful women who is willing to lie, to kill, and even to wage war against his homeland to get what he desires.” [3] He expressed similar views about the Prophet in two of his letters, one to Frederick II of Prussia in 1740 and the other to Pope Benedict XIV in 1745. Sometime after 1745, however, he read Boulainvilliers’ Vie de Mahomed, and it seems to have had a lasting impact on his perception of Prophet Muhammad (salAllahu alayhi wa sallam). Later in life, particularly in his historical writings such as the Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations (1756), Voltaire praised the Prophet as an effective and tolerant leader and a successful conqueror, though he still maintained that Prophet Muhammad was not divinely inspired but was “so carried away [by his success as a leader] that he believed himself inspired by God.” [4]

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) was yet another Enlightenment-era French philosopher who couldn’t help but comment on Prophet Muhammad (salAllahu alayhi wa sallam), and that too in his magnum opus, The Social Contract (1762). Muhammad, he said, was neither an imposter nor a sorcerer, but an admirable legislator who successfully combined spiritual and worldly power. [5] In 1787, Claude-Emmanuel Pastoret (1755-c. 1830), a French author and politician, published his Zoroaster, Confucius and Muhammad, in which he compared and contrasted the careers of the three Eastern religious “great men”, “the greatest legislators of the universe.” He defended Prophet Muhammad against the allegations commonly made against him, and praised the Qur‘ān for the way it upholds the unity of God (tawhīd). [6]

Henri de Boulainvilliers, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Claude-Emmanuel Pastoret all lived during the Enlightenment and all were French intellectuals, but Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), another Frenchman who was very interested in Prophet Muhammad (salAllahu alayhi wa sallam), came to the stage after the French Revolution and is remembered far more as a military and political leader than as an intellectual or historian. In May 1798, he set out towards the Egypt and Syria leading 55,000 men of the French navy in an effort to challenge British control over the area, which was officially still part of the Ottoman Empire. On July 1, 1798, before landing at Alexandria, he sent the following written declaration to the Egyptian people:

“In the name of God the Beneficent, the Merciful. There is no other God than God, [and] He has neither son nor associate to His rule. On behalf of the French Republic founded on the basis of liberty and equality, the General Bonaparte, head of the French Army, proclaims to the people of Egypt that for too long the beys [i.e. Ottoman governors] who rule Egypt insult the French nation and heap abuse on its merchants; the hour of their chastisement has come. For too long, this rabble of slaves brought up in the Caucasus and in Georgia [i.e. the ruling-class Mamluks of Egypt] tyrannizes the finest region of the world; but God, Lord of the worlds, [the] All-Powerful, has proclaimed an end to their empire. Egyptians, some will say that I have come to destroy your religion. This is a lie, do not believe it! Tell them that I have come to restore your rights and to punish the usurpers; that I respect, more than do the Mamluks, God, His prophet Muhammad and the glorious Qur‘ān… Qādī, shaykh, shorbagi, tell the people that we are true Muslims. Are we not the one who has destroyed the Pope [during the Italian Campaign of 1796-97] who preached war against Muslims? Did we not destroy the Knights of Malta, because these fanatics believed that God wanted them to make war against the Muslims?” [7]

This definitely sounds very much like the self-serving, propagandistic rhetoric that is always used by imperialists, but it shows Napoleon’s cultural and historical awareness and the way he used it to his advantage. It also shows that, far from vilifying Prophet Muhammad (salAllahu alayhi wa sallam) and trying to convince the Egyptian people that Islam was the cause of the tyrannical leadership from which he was supposedly here to liberate them, he actually used Islam to legitimize his cause. But nevertheless, this was most probably mere lip service. But many years later, as he was exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena after having lost the Napoleonic Wars, he wrote down his thoughts on Prophet Muhammad in his memoirs. Since there was no conceivable ulterior motive by this point for him to be saying about Prophet Muhammad what he did not actually believe, the following passage from his memoirs may show his genuine admiration for Prophet Muhammad:

“Arabia was idolatrous when Muhammad, seven centuries after Jesus Christ, introduced the cult of the God of Abraham, Ishmael, Moses and Jesus Christ. The Arians and other sects that had troubled the tranquility of the Orient had raised questions concerning the nature of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Muhammad declared that there was one unique God who had neither father nor son; that the trinity implied idolatry. He wrote on the frontispiece of the Qur‘ān: “There is no other god than God.”

He addressed savage, poor peoples, who lacked everything and were very ignorant; had he spoken to their spirit, they would not have listened to him. In the midst of abundance in Greece, the spiritual pleasures of contemplation were a necessity; but in the midst of the deserts, where the Arab ceaselessly sighed for a spring of water, for the shade of a palm where he could take refuge from the rays of the burning tropical sun, it was necessary to promise to the chosen, as a reward, inexhaustible rivers of milk, sweet-smelling woods where they could relax in eternal shade, in the arms of divine hūrīs with white skin and black eyes. The Bedouins were impassioned by the promise of such an enchanting abode; they exposed themselves to every danger to reach it; they became heroes. Muhammad was a prince; he rallied his compatriots around him. In a few years, his Muslims conquered half the world. They plucked more souls from the false gods, knocked down more idols, razed more pagan temples in fifteen years, than the followers of Moses and Jesus Christ did in fifteen centuries. Muhammad was a great man.” [8]

“Muhammad was a great man.” Boulainvilliers, Rousseau and Pastoret would definitely agree, though none of them are known to have ever practiced Islam. ‘Umar, Khālid, and ‘Amr would definitely agree as well, whether you asked them before they embraced Islam or afterwards. But what do all of them have in common? The answer, I would argue, was their enlightened, which provided them with certain values which shaped their understanding of the life of Prophet Muhammad (salAllahu alayhi wa sallam). They lived during periods of uncertainty and major social and intellectual shake-ups of society. The Frenchmen all lived during the Enlightenment, and so they challenged the traditional way of thinking about Prophet Muhammad using their shifting values (a shift towards objectivity when studying history, for example). The Arabs, for their part, were all relatively young at the time of the dawn of Islam, and therefore were not as caught up in the traditions of pre-Islamic Arabia as their elders were, so they challenged the traditional way of thinking about Prophet Muhammad as well, using their own shifting values (a shift from tribal identity to faith-based identity, for example).

The reminder in this for Muslims today is that not all those who oppose Islam do so for the same reason or in the same way. There are always certain trends, yes, but Muslims should remain keenly aware of non-Muslim individuals who are attaining enlightenment through social, cultural and intellectual shifts, because these shake-ups in history often present excellent opportunities for fulfilling the obligation of da’wah to Islam. ‘Umar, Khālid, and ‘Amr all received this da’wah; Boulainvilliers, Voltaire, Rousseau, Pastoret and Napoleon almost certainly did not. And we will never know, given their general admiration for the Prophet, how close these enlightened French disbelievers may have been to embracing Islam if only they had been properly invited to it.

Sources:

- Yasir Qadhi, “Seerah of Prophet Muhammed 3 – Why study the Seerah? & Pre-Islamic Arabia”, YouTube video, June 22, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4F5qzMI2IKs.

- Henri de Boulainvilliers, La vie de Mahomed (Amsterdam: P. Humbert, 1730); Boulainvilliers, The Life of Mahomet (London: W. Hinchliffe, 1731), 179-222.

- John Tolan, “European Accounts of Muhammad’s Life”, in Jonathan Brockopp (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 241.

- Voltaire, Essai sur les moeurs, chap. 6.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Du contrat social (Amsterdam: Marc Michel Rey, 1762), 303–304.

- Emmanuel Pastoret, Zoroastre, Confucius et Mahomet, comparés comme sectaires, législateurs, et moralistes; avec le tableau de leurs dogmes, de leurs lois et de leur morale (Paris: Buisson, 1787), 385, l. 1 and 234-236.

- Qtd. in Henri Laurens, L’Exp´edition d’Egypte, 1798–1801 (Paris: Seuil, 1997), 108.

- Napoléon Bonaparte, Campagnes d’Egypte et de Syrie (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1998), 140-141.

Image: Napoleon in Egypt (1863) by Jean-Léon Gérôme (https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/originals/f4/f3/41/f4f3415ec2e9bb7913c4d67931082bb7.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment